Reading the historian Arnold Toynbee’s lectures on the British Industrial Revolution, it is quickly apparent that conditions in England prior to 1760 were in many respects similar to those in developing countries today: Poor infrastructure and communication, lack of technological innovation, no division of labor, a focus on local commerce, and a weak banking system.1 Surprisingly, the modern study of religion and economics begins with Adam Smith’s An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776), an examination of conditions leading to the Industrial Revolution. In his book, Smith applies his innovative laissez-faire philosophy to several aspects of religion. However, Smith’s fundamental contribution to the modern study of religion was that religious beliefs and activities are rational choices. As in commercial activity, people respond to religious costs and benefits in a predictable, observable manner. People choose a religion and the degree to which they participate and believe (if at all).

Smith’s contribution to the study of religion is not simply theoretical. He held substantive views, for example, on the relationship between organized religion and the state. Smith argued strongly for a disassociation between church and state. Such a separation, he said, allows for competition, thereby creating a plurality of religious faiths in society.2 By showing no preference for one religion over others, but rather permitting any and all religions to be practiced, the lack of state intervention (short of violence, coercion, and repression) creates an open market in which religious groups engage in rational discussion about religious beliefs. This setting creates an atmosphere of “good temper and moderation.” Where there is a state monopoly on religion or an oligopoly among religions, one will find zealousness and the imposition of ideas on the public. Where there is an open market for religion and freedom of speech, one will find moderation and reason.

A contemporary of Smith (though they were not acquainted) and a public intellectual during the British Industrial Revolution, John Wesley had much to say about the relationship between religion and economic development, though his perspective differed radically from Smith’s. Wesley (1703–1791), a theologian and the founder of Methodism and the Holiness Movement, championed the two-way causation between religion and economic growth, preaching in 1744, “Gain all you can, Save all you can, Give all you can.” Later, in his famous sermon of 1760, “The Use of Money,” Wesley expounded upon these three points, emphasizing hard work, self-reliance, and mutual aid. Finally, just two years before his death (he lived to be 88), Wesley berated his congregants from the pulpit for their comfortable lifestyle and urged them to give away their fortunes. In the 45 years between these two sermons, Wesley’s followers, by working hard and saving, had raised themselves up into the comfortable middle class. Wesley understood very well the direct causal relationship between religious beliefs and productivity. He also understood well that wealth accumulation could weaken religiosity both in terms of beliefs and participation. Wesley concluded that economic growth was detrimental to religion. Is it? And, if so, must it be?

The two-way causation

Let us look at the two-way causation and, thereby, the relationship between religion and development. First, how does a nation’s economic and political development affect its level of religiosity? When we look at the effects of economic development on religion, we find that overall development — represented by per capita Gross Domestic Product (gdp) — tends to reduce religiosity.3 The empirical evidence supports, to a degree, the secularization thesis which holds that with increased income, people tend to become less religious (as measured by religious attendance and religious beliefs). Economic development causes religion to play a lesser role in the political process and in policymaking, in the legal process, as well as in social arrangements (marriages, friendships, colleagues). There are four primary indicators of the influence of economic development on religion.

Economic development implies a rising opportunity cost of participating in religious services and prayer.

Education. The more educated a person is, the more likely he is to turn to science for explanations of natural phenomena, with religion intended to explain supernatural phenomena and psychological phenomena for which there is no rational explanation. According to this view, the higher the levels of educational attainment, the less religious people will be (negative effect). On the other hand, an increase in education will also spur participation in religious activities, because educated people tend to appreciate social networks and other forms of social capital. Education increases the returns from networks and networking. On this view, religion is just another type of social capital (positive effect). Thus, we cannot conclude that richer societies are less religious because people are better educated.

Value of time (measured by effects on per capita GDP). Economic reasoning tells us that anything that raises the cost of religious activities would — ceteris paribus — reduce these activities. We know that economic development and participation in the workforce raise the value of a person’s time as measured by the value of market wages. Thus, economic development implies a rising opportunity cost of participating in time-intensive activities, such as religious services and prayer. Hence, people will participate less in religious activities because their time is now more valuable to them. So, as a country’s per capita gdp increases, we expect to see a decrease in participation in formal religious activities. Older people and young people — in other words, those persons with a low value of time — will tend to participate more in religious activities.

Life expectancy. People are living longer all over the globe, not just in industrialized countries. Longevity has been rising almost everywhere in the world. Since 1950, it has climbed by larger absolute and percentage amounts in poor countries. With people living longer, participation in certain religions will be low and then rise as the population ages.

Urbanization. Urbanization is another aspect of economic growth that is said to have a substantial negative effect on religious participation. Why? Because in urban areas religious activities compete with others, such as the symphony, theatre, museums, and volunteer activities. Thus, religion takes up your leisure time and competes with other leisure activities, not just work.

We know empirically by doing cross-country analysis that per capita gdp has a significantly negative effect on religion, both in terms of beliefs and participation. This tendency is gradual as countries grow richer. Furthermore, a steady pattern of secularization only applies to a few countries, such as Britain, France, and Germany. Although religiosity declines overall with economic development, the nature of the interaction varies with the dimension of development. For example, increased education has very different effects on religious participation and religiosity from rises in life expectancy or urbanization.

Second, how do religion and religiosity influence economic performance and the nature of political, economic, and cultural institutions? We find that, for a given level of religious participation, increases in core religious beliefs — notably belief in hell, heaven, and an afterlife — tend to increase economic growth. Our interpretation, reminiscent of Max Weber’s famous thesis in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, is that religious beliefs raise productivity by fostering individual traits such as honesty, work ethic, and thrift. In contrast, for given religious beliefs, increases in church attendance tend to reduce economic growth. We think that this negative effect reflects the time and resources used by the religion sector as well as adverse effects from organized religion on economic regulation — for example, restrictions on markets for credit and insurance. To put it another way, the main growth effect that we find is a positive response to an increase in believing relative to belonging (attending). Striking patterns of relatively high belief appear in the Scandinavian countries, Britain, and Japan. Although these countries are not generally viewed as religious, the belief levels are high when compared to the low levels of attendance at formal religious services. Countries with low levels of belief relative to religious participation are Latin American nations and India. We also have some evidence that the stick represented by the fear of damnation is more potent for growth than the carrot from the prospect of salvation.

Now let’s look at how religion influences the four primary indicators of economic development.

Education. We find that religious beliefs are compatible with increased education and knowledge. Religion is attractive to people with higher levels of educational attainment because religious beliefs can be neither proved nor disproved. Educated people engage in speculative reasoning and are better able to think abstractly. Therefore, religion can offer something to them.

Religious beliefs matter for economic outcomes. They reinforce character traits such as hard work, honesty, thrift, and the value of time. Otherworldly compensators — such as belief in heaven, hell, the afterlife — can raise productivity by motivating people to work harder in this life. The Calvinist view of salvation through grace posits that since you cannot know whether or not you are saved, you work conscientiously your whole life (a life of good works). Religious rewards — such as absolution of sin, earning salvific merit by giving to charity — also motivate people to work hard and cultivate virtuous behavior.

...Full-text available, click here. .

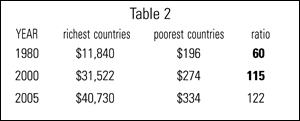

The message the Economist conveys with these two charts is that critics of recent globalization are mendacious or confused when they complain of inequitable growth: Only when the population size of countries is ignored (as in the top chart) can it appear as though global economic growth is benefiting the rich disproportionately. As soon as population size is taken into account (as in the bottom chart) it becomes clear that the poor are benefiting mightily—the rise of China and India is living proof of this. A further message here conveyed is that globalization’s supporters, such as the Economist, care about poverty and inequity and would not be such ardent supporters if the poor were not benefiting along with the rich.

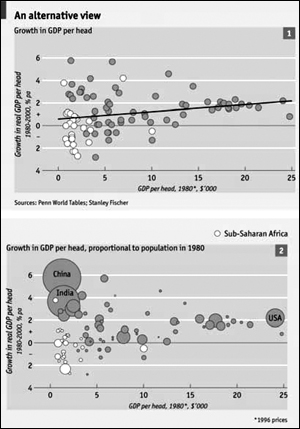

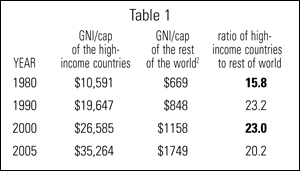

The message the Economist conveys with these two charts is that critics of recent globalization are mendacious or confused when they complain of inequitable growth: Only when the population size of countries is ignored (as in the top chart) can it appear as though global economic growth is benefiting the rich disproportionately. As soon as population size is taken into account (as in the bottom chart) it becomes clear that the poor are benefiting mightily—the rise of China and India is living proof of this. A further message here conveyed is that globalization’s supporters, such as the Economist, care about poverty and inequity and would not be such ardent supporters if the poor were not benefiting along with the rich. The increase in inequality is even more pronounced at the extremes. Define the poorest and the richest countries in any year as groups of countries that each contains 10 percent of the world’s population.

The increase in inequality is even more pronounced at the extremes. Define the poorest and the richest countries in any year as groups of countries that each contains 10 percent of the world’s population.